An article in a recent issue of North & South Magazine that focusses on housing in Cromwell says the town is experiencing rapid growth and interest from buyers. It interviews a few ‘new’ locals who have recently made Cromwell home, giving some great insights into life in Otago’s fastest-growing town.

Cromwell has known booms and busts since it was founded by gold miners. Now there’s a new rush going on, with people flocking to the town once again – and Cromwell is struggling to keep up!

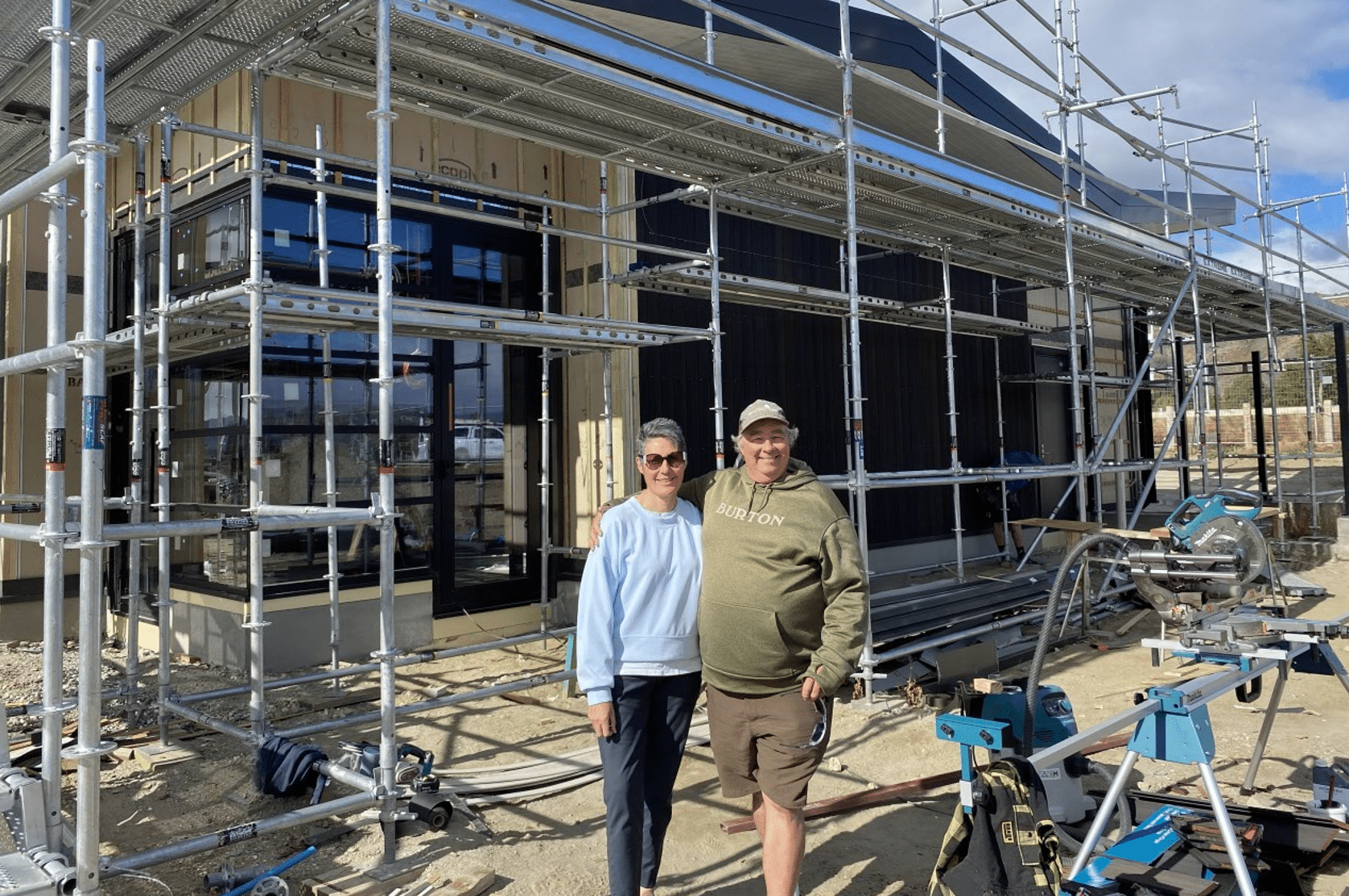

Today, the town’s boundary is bulging, its margins expanding as it copes with rapid development. There are new subdivisions at all compass points; new industry; new horticulture ventures planned. It’s growing and groaning, booming but creaking. These are good times for Cromwell in so many ways, but they come with concerns and quandaries.

Cromwell was born with a boom, created after Horatio Hartley and Christopher Reilly discovered gold near the confluence of the Kawarau and Clutha rivers in 1862. When the miners moved on, it became a service town at the junction of several highways, its land used for farming and fruit growing. Another boom occurred in the 1980s with the construction of the Clyde dam, down-river on the Clutha. Cromwell housed most of the workers for the 10 years it took to pour a million cubic metres of concrete and build the country’s largest hydro-electric dam.

But Cromwell’s transformation at that time went far beyond being swamped with single men. The dam formed Lake Dunstan and flooded parts of the old town. Its commercial centre was shifted away from the river, and a completely new CBD built. Nearby, a colossal fruit sculpture was erected – an apple, pear, nectarine and apricot hoisted on giant girders, symbolising the area’s biggest industry, and becoming the town’s much-photographed emblem. Lonely Planet once described it as a “spectacularly ugly giant fruit salad”, but as a local politician responded, “It’s ours, we’ve got it, and we love it.”

For a while after the dam, Cromwell drifted, though the arrival of the wine industry in the 90s provided a valuable fillip, with rabbit-riddled land suddenly prized for pinot noir.

But even with the glamour of boutique wineries, Cromwell still played third fiddle to Queenstown and Wānaka – the ugly sibling, ignored by tourists.

And it’s still that way to an extent. But as Queenstown and Wānaka have become tourism darlings and been inundated by those prepared to pay a fortune to live in chocolate box surroundings, Cromwell has reaped downstream economic rewards. Those unable to afford a house in Queenstown have looked to Cromwell for real estate sanity. Others have cashed up their tourist townhomes and seen their money go much further in Cromwell. Likewise, businesses have found cheaper commercial properties in Cromwell and shifted operations there. Cromwell’s population of around 5000 is predicted to double in the next 30 years.

Mike White – 27th February 2019